Concept: The Action Potential

Cardiac cells are encased by a cell membrane. Differences in the concentration of

charged particles (called ions) inside and outside the

cell result in a membrane potential - a difference in electric potential

across the membrane. The Action Potential refers to the change in this membrane potential

during excitation, illustrated below.

Animation: The Action Potential. Left panel shows a schematic of a cell with different types

of ion and the channels which allow them to pass (coloured circles and channels), and the

right panel shows the membrane potential at different stages of the Action Potential.

Animation: The Action Potential. Left panel shows a schematic of a cell with different types

of ion and the channels which allow them to pass (coloured circles and channels), and the

right panel shows the membrane potential at different stages of the Action Potential.

As ions flow through these ion channels, the movement of charge creates ionic currents which can change the membrane potential. Because the opening and closing of ion channels can also be controlled by the membrane potential, the currents can be coordinated to create the shape of the Action Potential.

There are multiple types of ion channel, each associated with specific ions (sodium, potassium, calcium and others).

"Inward" currents are those where positive charge enters the cell (yellow and red in the animation) - they make the membrane potential more positive, which we call “depolarisation”: Larger inward currents generally mean greater excitability and longer durations of the Action Potential.

"Outward" currents are those where positive charge leaves the cell (blue in the animation) – they make the membrane potential more negative, which we call "repolarisation": Larger outward currents generally mean lower excitability and shorter duration.

The balance of multiple different currents, controlled by the expression (amount of) each type of ion channel, can therefore control Action Potentials with different shapes and properties to match the varying requirements of cardiac function in different animals and under different conditions (e.g. rest versus exercise).

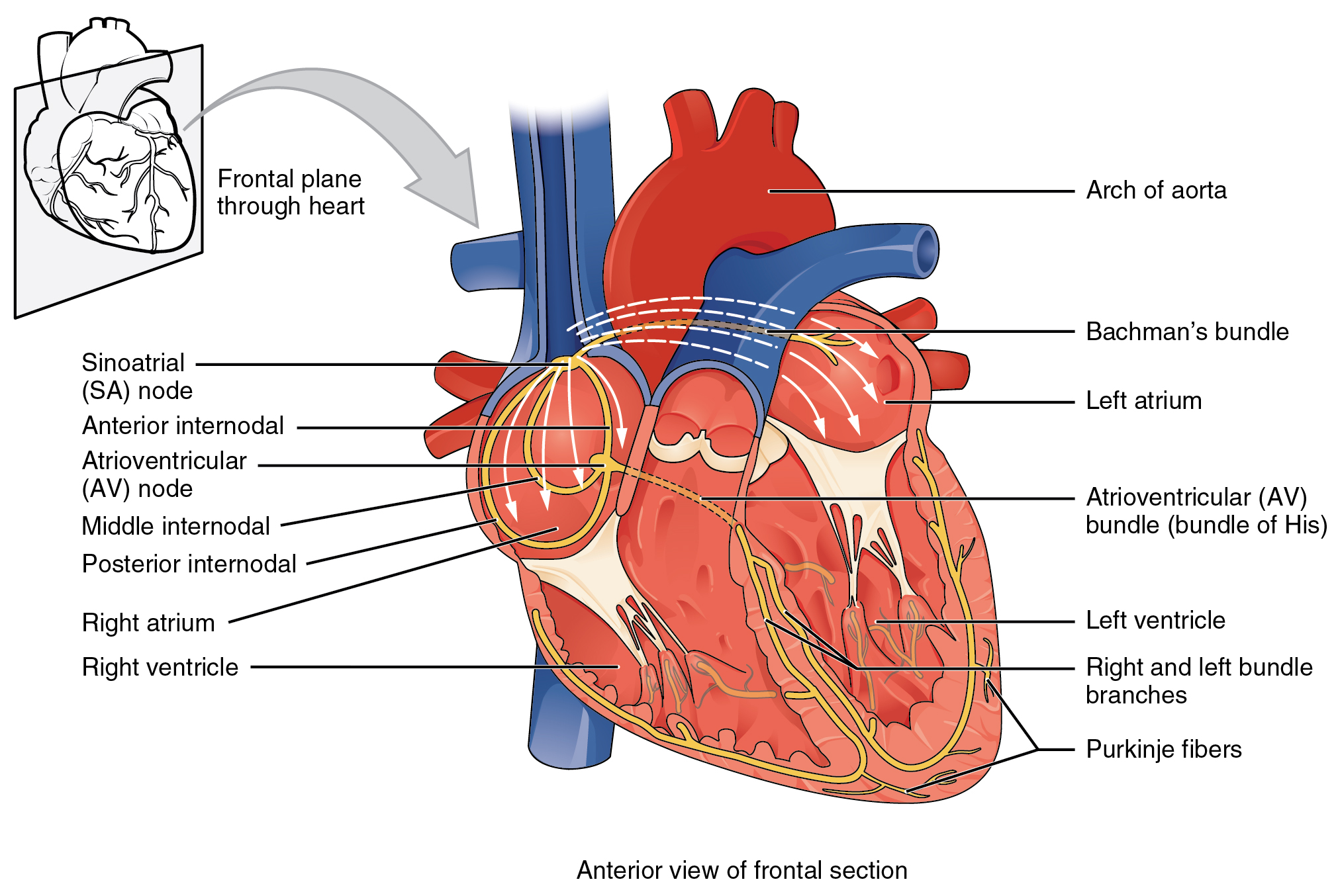

Illustration of the cardiac conduction system. Source:

Illustration of the cardiac conduction system. Source:  Animation: The intracellular Ca2+ handling cycle. Left panel shows a schematic of the cellular

components involved in Ca2+ handling: the surface membrane and T-tubules (TT); the intracellular

Ca2+ store called the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (SR; blue-green); the contractile proteins (myofilaments); the

Ca2+ carrying flux channels responsible for the initial influx (red), intracellular Ca2+

release (blue), SR refilling (yellow) and Ca2+ extrusion (green). Arrows indicate the timing and direction

of fluxes. Green areas indicate high Ca2+ concentration.

The right panel shows the Action Potential (blue) and whole-cell Ca2+ transient (orange)

at each phase.

Animation: The intracellular Ca2+ handling cycle. Left panel shows a schematic of the cellular

components involved in Ca2+ handling: the surface membrane and T-tubules (TT); the intracellular

Ca2+ store called the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (SR; blue-green); the contractile proteins (myofilaments); the

Ca2+ carrying flux channels responsible for the initial influx (red), intracellular Ca2+

release (blue), SR refilling (yellow) and Ca2+ extrusion (green). Arrows indicate the timing and direction

of fluxes. Green areas indicate high Ca2+ concentration.

The right panel shows the Action Potential (blue) and whole-cell Ca2+ transient (orange)

at each phase.

Image adapted from

Image adapted from  Animation: Illustration of re-entrant excitation. The animation shows a 2D idealised sheet of cardiac tissue,

representing, for example, the surface of the heart. The colours (purple-red-yellow) indicate the local

voltage (a surrogate for contraction, as the voltage is the contractile trigger). On the left is a representation

of normal behaviour: excitation originates from a single source and propagates through the tissue uniformly;

there are significant rest periods between each excitation.

On the right is an example of a simple

form of re-entry - a "stable scroll wave". This type of excitation is rapid (note the minimal resting/relaxation

period between each cell's excitation time) and, because it self-perpetuates, it is independent of the

primary pacemaker.

Animation: Illustration of re-entrant excitation. The animation shows a 2D idealised sheet of cardiac tissue,

representing, for example, the surface of the heart. The colours (purple-red-yellow) indicate the local

voltage (a surrogate for contraction, as the voltage is the contractile trigger). On the left is a representation

of normal behaviour: excitation originates from a single source and propagates through the tissue uniformly;

there are significant rest periods between each excitation.

On the right is an example of a simple

form of re-entry - a "stable scroll wave". This type of excitation is rapid (note the minimal resting/relaxation

period between each cell's excitation time) and, because it self-perpetuates, it is independent of the

primary pacemaker.

Animation: Illustration of the concept of the refractory period in single cells.

This shows three cases where the first beat is identical, but the timing of the next stimulus

varies (late - purple; just outside refractory period - blue; just inside refractory period - orange).

The dotted line shows where the amplitude threshold is.

Animation: Illustration of the concept of the refractory period in single cells.

This shows three cases where the first beat is identical, but the timing of the next stimulus

varies (late - purple; just outside refractory period - blue; just inside refractory period - orange).

The dotted line shows where the amplitude threshold is.

Animation: Illustration of the concept of the refractory period in tissue.

On the left is shown the local voltage in a strand of cardiac cells (colours purple-red-yellow indicate

local voltage). The stimulus is applied to the top edge,

and propagates along the strand to the bottom edge. On the right are traces of the voltage from cells taken

from different parts of the strand (indicated by the markers on the strand) - by the stimulus site (blue)

and towards the far end (red).

Animation: Illustration of the concept of the refractory period in tissue.

On the left is shown the local voltage in a strand of cardiac cells (colours purple-red-yellow indicate

local voltage). The stimulus is applied to the top edge,

and propagates along the strand to the bottom edge. On the right are traces of the voltage from cells taken

from different parts of the strand (indicated by the markers on the strand) - by the stimulus site (blue)

and towards the far end (red). Animation: Illustration of unidirectional conduction block due to heterogeneity. Two stimuli are applied to

a homogeneous and heterogeneous sheet; the first is from the upper edge. It propagates uniformly

through the tissue in both cases. The second is applied to a small region in the centre, at the junction

between the region with a short AP (top half) and the one with a long AP (bottom half) in the heterogeneous case. Note

that you can see this difference in the heterogeneous case following the first stimulus,

by the bottom half staying active for longer than the top.

Animation: Illustration of unidirectional conduction block due to heterogeneity. Two stimuli are applied to

a homogeneous and heterogeneous sheet; the first is from the upper edge. It propagates uniformly

through the tissue in both cases. The second is applied to a small region in the centre, at the junction

between the region with a short AP (top half) and the one with a long AP (bottom half) in the heterogeneous case. Note

that you can see this difference in the heterogeneous case following the first stimulus,

by the bottom half staying active for longer than the top.